Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendments: A Bad Precedent In Tô Lâm’s ‘Rising Era’

A Party-Driven Constitutional Process

The Vietnamese Magazine summarizes the latest updates, comprehensive background information, and expert commentary on the ongoing “Barbie” and BlackPink situation in Vietnam.

This article was published in Luat Khoa Magazine on July 10, 2023. Quynh-Vi Tran translated this into English.

On July 3, Vietnam's Cinema Bureau publicly announced that Barbie would be prohibited from screening in Vietnam. This decision was reached by the National Film Evaluation and Classification Council, primarily due to a scene allegedly featuring the nine-dash line. The Bureau refrained from disclosing specific details regarding the scenes in question. [1]

Simultaneously, a pro-government Facebook page called Tifosi posted a supportive statement endorsing the ban. This post garnered substantial attention, amassing approximately 15,000 likes and nearly 500 shares as of July 9. [2]

Subsequently, an image from the movie, displaying a vague, scribbled map, began circulating on the internet. Within this image, two dashed lines were visible. Among the public, divergent opinions emerged regarding the interpretation of these lines. Some believed one of the dashed lines represented the Nine-Dash Line in the East Sea (South China Sea), while others argued that it was situated in Greenland or North America, unrelated to the East Sea. The second dashed line appeared within the Asian region of the map. [3]

On July 7, Warner Bros. responded by stating that the map depicted in the film was merely a product of childish drawings devoid of any intentional political implications. [4]

On the same day, Tran Thanh Hiep, the chairman of the National Film Appraisal and Classification Council, told VietNamPlus that the map image in question appeared multiple times throughout the movie in various scenes. He emphasized that the issue extended beyond the viral scene and asserted that the map's ambiguity made it susceptible to interpretation and that the violation was apparent. The Cinema Bureau reiterated its stance, confirming that it had not altered its position. [5] [6]

The international media has been closely monitoring the developments surrounding this case.

In response, the Philippine Film and Television Film Appraisal and Classification Board announced that it is evaluating the “Barbie” film. [7]

Following the eruption of protests regarding the controversy over the nine-dash line, the public outcry shifted to another highly anticipated entertainment event - the upcoming BlackPink performance in Vietnam, scheduled for July 29 and 30.

In the aftermath of the “Barbie” case, numerous Vietnamese viewers made a startling discovery. They found that the Facebook page of the event organizer, IME Music Co., Ltd (IME Vietnam), was linked to the parent company's website. That website featured a copy of the nine-dash line. [8]

The parent company, iMe Entertainment Group, is headquartered in Beijing, China. [9]

The boycott movement swiftly spread across Vietnamese online communities, gaining momentum and support. [10]

On July 6, Brian Chow, director of IME Vietnam, apologized, acknowledging the importance of respecting the sovereignty and culture of all countries where IME operates. He pledged to promptly review and replace inappropriate images with ones suitable for the Vietnamese audience. He expressed sincere regret for the unfortunate misunderstanding. [11]

However, the wave of censorship and boycotts did not stop with BlackPink. It continued to surge, encompassing the movie "Flight to You." On July 9, the Cinema Bureau officially requested Netflix and FPT Play to remove the film due to the presence of the nine-dash line in multiple episodes of the series. [12]

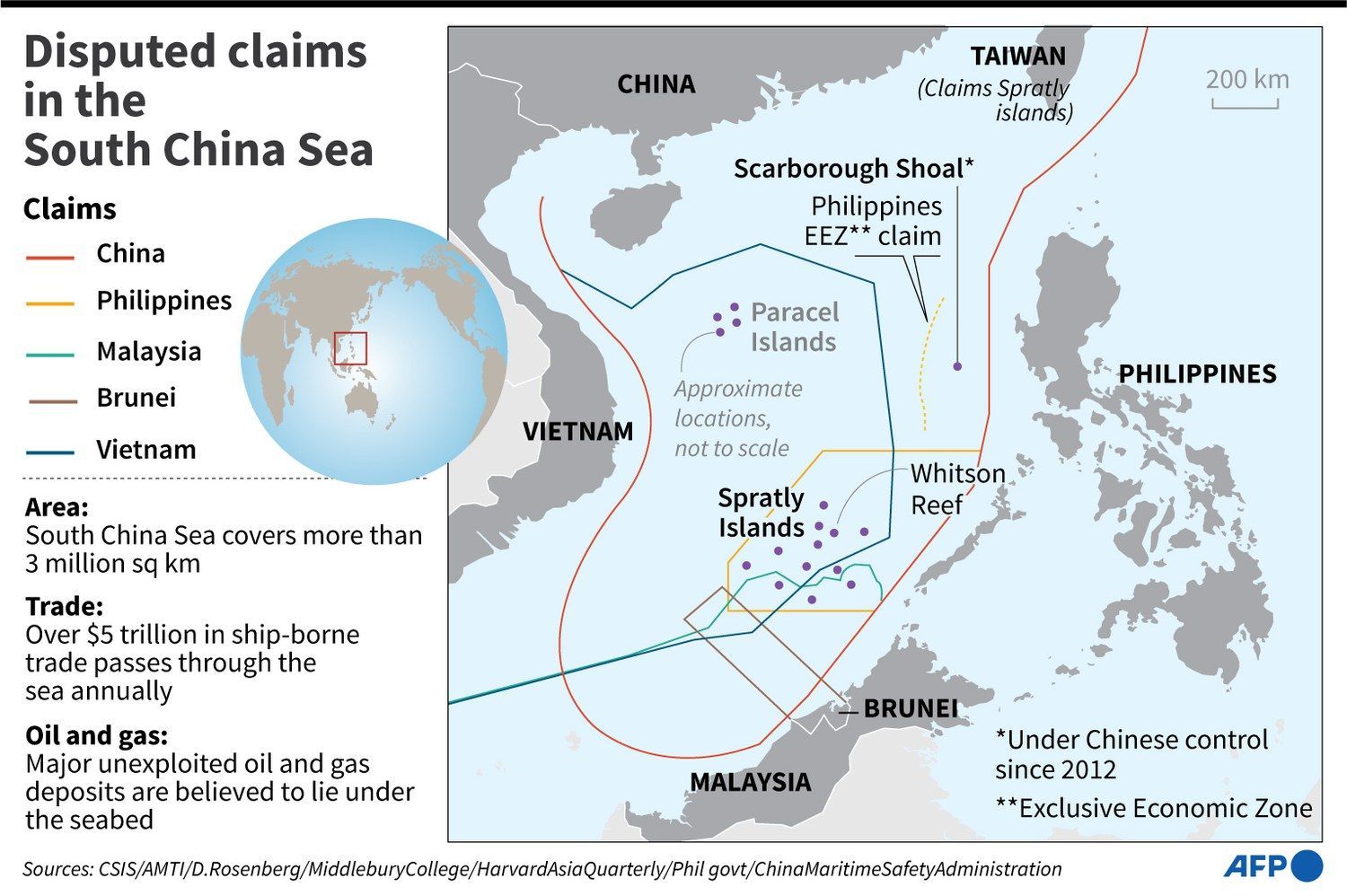

In Vietnamese, people commonly refer to the nine-dash line as Đường Lưỡi Bò, a direct translation of the “cow’s tongue line,” which encompasses China's expansive territorial claim in the East Sea (also known as the South China Sea). This claim extends over 90% of the East Sea area, overlapping with the territorial claims of neighboring coastal states, including Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Brunei.

The U-shaped line first appeared on a 1947 map published by the government of the Republic of China (ROC) [13]. Following the defeat of the Kuomintang in 1949, the Communist Party of China established the People's Republic of China, which further solidified and formalized this claim. In May 2009, China submitted a map to the United Nations asserting its sovereignty over the disputed region in response to claims made by Vietnam and Malaysia. [14] It was during this event that the nine-dash line garnered widespread attention among the general public.

On July 12, 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) based in the Netherlands issued a landmark ruling declaring the U-shaped line invalid under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) of 1982. The ruling came after a lengthy process of over three years, prompted by a complaint filed by the Philippine government [15]. Notably, Vietnam did not participate in the lawsuit and has yet to take legal action against China regarding the nine-dash line or the broader disputes in the East Sea.

For many years, China has included the nine-dash line on the passports issued to its citizens, showcasing its persistent assertion of sovereignty over the disputed waters.

The nine-dash line remains a contentious issue, fueling tensions and disputes among nations in the region as each coastal state seeks to safeguard its own territorial claims in the East Sea.

As the controversy surrounding the nine-dash line unfolds, various currents of opinion have emerged within the public discourse, shedding light on the complex dynamics at play.

Dinh Kim Phuc, a respected researcher of the East Sea, expressed concerns regarding the potential implications of the cow’s tongue line's appearance in the movie to RFA Vietnamese. According to Phuc, if the film indeed showcases the controversial imagery and is allowed to be screened throughout Vietnam, it could inadvertently lend legitimacy to China's sovereignty claims in the East Sea. Phuc's remarks highlight the sensitive nature of the issue and the need for caution. [16]

A reader, sharing thoughts on Thanh Nien Newspaper Online, voiced support for the ban on the movie. The commenter went as far as suggesting that if the production company persists in bringing such films to Vietnam, a blanket ban should be imposed on all of their works. The comment reflects a firm stance on national sovereignty, advocating for zero compromises in territorial disputes. [17]

Professor Carlyle Thayer, an expert on Vietnamese politics, offered his opinion, asserting that the reaction to the film might be excessive and could divert attention away from more pressing issues, such as China's assertive actions at Tu Chinh Shoal. Thayer's statement draws attention to the broader geopolitical context and calls for a measured approach to addressing the complexities of the East Sea disputes. [18]

Michael Caster, a free speech expert, emphasized the inherently political nature of maps and borders, which often carry historical trauma. He criticized knee-jerk reactions that stifle open discussion and stressed the importance of thoughtful and nuanced responses in pursuing justice. Caster's perspective highlights the significance of fostering an environment conducive to open dialogue and understanding. [19]

These diverse viewpoints underscore the multifaceted nature of the issue and the ongoing debate surrounding the nine-dash line controversy, with stakeholders from various backgrounds expressing their concerns, opinions, and calls for prudence in navigating the complex East Sea disputes.

While the Vietnamese government and mainstream media have consistently voiced their opposition to the U-shaped line recently, there are additional protest activities that have received little or limited coverage. Remarkably, some individuals engaged in these activities have faced arrest and imprisonment for over a decade.

In 2011, a significant anti-China protest movement swept across Vietnam during the summer months, featuring a total of 11 political rallies of different sizes held in prominent cities like Hanoi, Saigon, and other localities [20]. Notably, one symbol that gained prominence during this movement was a t-shirt design that became akin to a protest uniform. The shirt featured a crossed-out nine-dash line with the slogan "No to U-line, Yes to UNCLOS." Subsequently, other t-shirt models with similar sentiments emerged.

The initiation of the No-U shirt can be traced back to the Saigon Tiep Thi newspaper, which introduced it during the peak of the protest movement. However, in February 2014, the newspaper faced closure by the Ministry of Information and Communications [21]. This action further illustrates the challenges faced by dissenting voices in Vietnam.

While these protest activities and expressions of opposition may have received limited attention in mainstream narratives, they highlight the ongoing resistance against the nine-dash line and signify the persistence of individuals striving to make their voices heard. The arrests and the closure of Saigon Tiep Thi underscore the extent to which the authorities have sought to control and suppress dissenting political viewpoints in Vietnam.

During the protest movement against the nine-dash line, numerous individuals faced severe consequences, with arrests and administrative detentions being common. The authorities employed various tactics, including monitoring, harassment, and even physical violence, to suppress the movement.

The No-U shirt, a potent symbol of opposition, became a sensitive item. Merely wearing or printing this shirt could result in arrest or harassment by the police [22]. The authorities demonstrated a solid reaction to any display of the shirt, further highlighting their efforts to stifle dissenting voices.

Following the protest movement, football clubs named No-U emerged in cities such as Hanoi and Saigon. However, these clubs faced continuous monitoring by the police. In some cases, pressure from law enforcement led to the cancellation of contracts, resulting in matches being unable to occur [23]. Such actions underline the extent of surveillance and control the authorities exert over activities associated with the protest movement.

Despite intermittent eruptions of anti-China protests and objections to the nine-dash line claim since 2011, the government has swiftly suppressed these demonstrations. State media has mainly refrained from covering these events, and if any information does emerge, it tends to portray the protesters as lawbreakers, aligning with the government's narrative.

The crackdown, surveillance, and limited media coverage surrounding these protests demonstrate the authorities' concerted efforts to maintain control and silence dissenting voices challenging the nine-dash line claim and expressing opposition to Chinese assertiveness in the region.

Disclaimer: The following comments represent one perspective among many. We welcome feedback and criticisms and encourage readers to share their thoughts via email. We may include some noteworthy comments in future publications.

The maps depicted in the “Barbie” movie that are being shared online by netizens bear no resemblance to real-world maps, making it extremely challenging to connect them to the actual nine-dash line. The decision by film censors to impose a ban based on this map appears forced, highlighting the typical arbitrariness seen in our country's censorship agencies and law enforcement in general.

The reaction of the Cinema Bureau and a significant portion of the public once again underscores the deep-seated anti-China sentiment embedded in Vietnamese political culture. This sentiment is so profound that even in situations with considerable ambiguity, the authorities opt for the politically safe choice: to ban the offending material.

The decision-making process here is transparent - it is better to ban even if there is a mistake rather than risk omission. The government knows that even if the ban is erroneous, most of the public will still express support or sympathy. This overreaction pleases their superiors, leaving little room for criticism.

Cases like this enable the Vietnamese government to exploit the nationalist sentiment surrounding sovereignty issues, bolstering the legitimacy of the speech censorship regime in our country. By enlisting public support for censoring less controversial content, they demonstrate to the public the perceived utility of censorship, effectively countering criticisms of the policy. After grappling with anti-Chinese nationalism in the first 15 years of the 21st century, the government has learned to harness this sentiment to serve its own interests.

The direct parties impacted by the decision to censor “Barbie” are the film distribution companies and cinemas. In theory, the studios could challenge the Cinema Bureau's administrative decision in court, seeking a rejection. However, in practice, Vietnam's courts lack judicial independence and often render decisions under the instruction of the Communist Party. It is unlikely that the film distributors would prevail in such a case.

While the government has exerted a heavy-handed approach in interfering with the screening of the “Barbie” movie, any civil action against the nine-dash line would likely be deemed illegal.

For instance, if a group of citizens were to print t-shirts to protest against the “Barbie” movie or express opposition to the nine-dash line, they would likely face arrest, confiscation of their belongings, and potential fines for administrative violations.

This is not a theoretical proposition but an established fact that has persisted for many years. It exemplifies what is commonly referred to as the "patriotic monopoly" in Vietnam.

1. Phim Barbie bị cấm chiếu rạp Việt vì “đường lưỡi bò.” (2023, July 3). vnexpress.net. https://vnexpress.net/phim-barbie-bi-cam-chieu-rap-viet-vi-duong-luoi-bo-4624523.html

3. Bản đồ đứt đoạn phim Barbie xuất hiện nhiều lần, gây suy diễn. (n.d.). VietnamPlus. Retrieved July 7, 2023, from https://www.vietnamplus.vn/ban-do-dut-doan-phim-barbie-xuat-hien-nhieu-lan-gay-suy-dien/873592.vnp

4. Broadway, D. (2023, July 7). Warner Bros defends “Barbie” film’s world map as “child-like.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/lifestyle/warner-bros-defends-barbie-films-world-map-child-like-2023-07-06/

5. Ibid [3]

6. Barbie cãi về “đường lưỡi bò”, Cục Điện ảnh vẫn giữ lệnh cấm. (2023, July 7). TUOI TRE ONLINE. https://tuoitre.vn/barbie-cai-ve-duong-luoi-bo-cuc-dien-anh-van-giu-lenh-cam-20230707105033545.htm

7. Westerman, A. (2023, July 7). After Vietnam, the Philippines could be next to ban “Barbie.” Here’s why. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2023/07/06/1186178724/barbie-movie-philippines-vietnam-china-map

8. Chi T. (2023, July 9). Vụ BTC concert BlackPink tại Việt Nam dính đến ‘đường lưỡi bò’ thu hút truyền thông quốc tế. thanhnien.vn. https://thanhnien.vn/vu-btc-concert-blackpink-tai-viet-nam-dinh-den-duong-luoi-bo-thu-hut-truyen-thong-quoc-te-185230709030641338.htm

9. See: https://www.linkedin.com/company/ime-entertainment-group-asia/about/

10. VN: Tẩy chay đêm nhạc Blackpink, phim Barbie vì “đường lưỡi bò” là yêu nước? (2023, July 7). BBC News Tiếng Việt. https://www.bbc.com/vietnamese/articles/c2xk0rpp818o

11. BTC show Blackpink xin lỗi vì hình ảnh “đường lưỡi bò” trên website. (2023, July 7). vnexpress.net. https://vnexpress.net/btc-show-blackpink-xin-loi-vi-hinh-anh-duong-luoi-bo-tren-website-4626075.html

12. Yêu cầu Netflix, FPT Play gỡ phim Trung Quốc “Flight to you” vì có “đường lưỡi bò.” (2023, July 9). TUOI TRE ONLINE. https://tuoitre.vn/yeu-cau-netflix-fpt-play-go-phim-trung-quoc-flight-to-you-vi-co-duong-luoi-bo-20230709095019519.htm

13. Zhen, L., & Zhen, L. (2018, September 18). What’s China’s ‘nine-dash line’ and why has it created so much tension in the South China Sea? South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy-defence/article/1988596/whats-chinas-nine-dash-line-and-why-has-it-created-so

14. Chapter 10: The South China Sea Tribunal – Law of the Sea. (n.d.). https://sites.tufts.edu/lawofthesea/chapter-ten/

15. Tòa trọng tài phán quyết: Đường lưỡi bò vô giá trị. (2017, July 31). TUOI TRE ONLINE. https://tuoitre.vn/duong-luoi-bo-vo-gia-tri-1136023.htm

16. Rfa T. S. (2023b, July 4). Việt Nam cấm chiếu phim Barbie vì có hình ‘đường lưỡi bò’: nhạy cảm thái quá hay cẩn tắc vô áy náy? Radio Free Asia. https://www.rfa.org/vietnamese/in_depth/vn_bans_barbie-07042023074256.html

17. Chi T. (2023a, July 8). Khán giả phản đối Warner Bros., ủng hộ việc cấm chiếu ‘Barbie’ tại Việt Nam. thanhnien.vn. https://thanhnien.vn/khan-gia-phan-doi-warner-bros-ung-ho-viec-cam-chieu-barbie-tai-viet-nam-185230708135713302.htm

18. Ibid [16]

19. Scott, L. (2023, July 8). No Barbie Girl in Vietnam’s World. VOA. https://www.voanews.com/a/no-barbie-girl-in-vietnam-s-world-/7171971.html

20. Nhìn lại Phong trào Biểu tình Hè 2011. (2011, September 4). BBC News Tiếng Việt. https://www.bbc.com/vietnamese/vietnam/2011/09/110903_viet_summer_protest_analysis

21. Rfa M. L. B. T. V. (2020, October 11). Sự đóng cửa của một tờ báo. Radio Free Asia. https://www.rfa.org/vietnamese/in_depth/the-closing-of-a-newspaper-ml-02282014071101.html

22. Rfa. (2020, October 11). ‘NoU’: chiếc áo mang biểu tượng yêu nước! Radio Free Asia. https://www.rfa.org/vietnamese/in_depth/le-hieu-dang-club-sent-an-open-letter-about-the-shirts-bearing-the-patriot-symbol-11152019124235.html

23. The Economist. (2019, December 12). The Vietnamese football club that defies China. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/asia/2019/12/12/the-vietnamese-football-club-that-defies-china

Vietnam's independent news and analyses, right in your inbox.